Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen.I am honoured to be invited here to talk to you today.Thank you very much for this opportunity.

The title, gHumanitarian and Medical Aidh, is so big that it tends to end in abstract arguments. Instead, I would like to talk about it by giving concrete examples of what I have seen and what I have done and by summarizing the Peshawar-kaifs activities carried out in Peshawar, Pakistan, and in Afghanistan for the past 22 years.

As you know, the Taliban regime fell under the U.S. attacks five years ago. Soon after that, Afghanistan became a land of lawlessness and anarchism instead of becoming a better place to live. The current situation in Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan, can be compared to a small boat floating aimlessly on a sea of magma in a crater. Many warn that, if the foreign troops withdrew from Kabul now, the capital wouldnft last even for a week.

Immediately after the collapse of the Taliban regime, a number of international aid organizations rushed to Kabul. Five years later, the majority of the NGOs operating in Afghanistan are still concentrated in Kabul, protected by the international troops. As a result, the information about Afghanistan that people are getting outside the country is mainly provided from Kabul City, a quite exceptional place in Afghanistan. What I actually see and feel in the countryfs rural areas is the opposite of what people outside Afghanistan are being informed of.

Nevertheless, since the U.S. invaded Iraq, more than half the aid and media organizations located in Afghanistan moved on to Iraq, and international concern over Afghanistan has faded away. I hope my lecture today will be informative enough to help you better understand the true and current situation in Afghanistan.

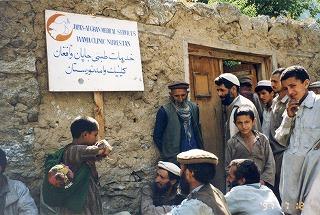

Peshawar-kai has its local base in Peshawar, a north-western city of Pakistan, and we operate in both Pakistan and Afghanistan. Currently, we have three clinics in Afghanistan which have been operating for over 16 years. We also run a clinic in northern Pakistan in addition to our main hospital in Peshawar. We have a total of 80 medical staff working at these facilities.

|

| £PMS clinic |

Last year, we treated 100,000 patients in total. In addition to medical work, we run a water supply programme. At our branch office in Jalalabad, Afghanistan, we have additional 80 staff working exclusively for this programme. Afghanistan has been severely hit by drought for the past six years and people are struggling with scarce water sources. I will later explain how we, a medical aid organization, decided to commit ourselves to a water supply programme.

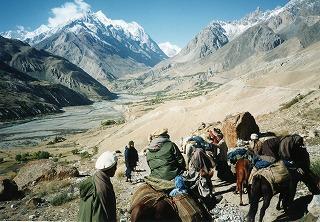

Now, let me mention some facts on Afghanistan which are not widely known. The area of Afghanistan is twice as large as that of Japan. The countryfs population is approximately 20 million. The majority of its land is dominated by the Hindu Khush Mountains that are 6,000 to 7,000 meters high. Obviously, it takes us quite a long time to cover numerous valleys spread across the mountainous area. For example, it could take us a whole week on a horseback to travel from our clinic to a patientfs home in a remote village. As you can imagine from this example, it takes a lot of time to accomplish anything over there. Regions and districts are physically divided by these massive mountains, keeping them isolated from one another. In each region and district, different ethnic groups live together, leading self-sufficient lives.

|

| £high mountains, horse ride |

Afghanistan is part of the arid region of Central Asia. More than 90% of its population depends on farming and cattle breeding for a living. Snow plays a crucial role there.

In Afghanistan, there is a proverb that says, gOne can live without money, but not without snow.h It is true. Snowfall during the winter, along with the glaciers from tens of thousands of years ago, produces water streams when it melts in summer, promising a good harvest in areas along the rivers. Humans, animals and plants around the Hindu-Khush Mountains have enjoyed the benefit of this water for a long, long time.

Snow is literally a lifeline for the Afghan people. However, in recent years, snow has been disappearing from these mountains, presenting a serious problem to the population.

Global warming is a major factor that is causing the drought in this region.

Most Afghans are devout Muslims. Mosques can be seen everywhere in villages and towns throughout the country. Islam is not only their belief but it is also their way of life. It provides the basis for their ethics, cultures and traditions. People belong to local communities as well as mosques and have moral obligations toward one another.

|

| £cattles,mosque |

Often times, troubles are solved by a local eldersf council called gJirgah at a mosque. Afghan communities are completely self-sufficient and self-governing societies where residents respect unwritten common laws. They donft, and perhaps donft need to, have modern police force or psychiatric hospitals in their communities. At the same time, Afghans show quite high tolerance toward authorities of time as long as their core values are honoured. Another aspect that stands out about Afghan people is their solidarity. Afghan men are strongly united by the blood and the territorial bond, and they act fearlessly to protect their own people and land. Afghans are quite an independent and brave people. The Afghans put higher priority on their traditions than on new rules introduced by the central government. This part of Afghan way of thinking is totally different from that of Westerners and, as a result, foreigners often find it difficult to understand these people.

The huge gap between the rich and the poor is also a big problem in Afghanistan. For example, wealthy Afghans can easily fly to London, Tokyo or New York to seek better medical treatment, while poor Afghans are dying, being unable to afford medicines that cost only a few dollars. With this example, you may understand why simply bringing advanced medical equipment and facilities wouldnft solve the problems there. The big challenge we face in Afghanistan is how to benefit the maximum number of people with the minimum amount of money. That is why it is very important for us to identify the real local needs and come up with proper arrangements so what we do will truly benefit the deprived people.

|

| £farmers |

I was assigned to the leprosy department of a Christian Hospital in Peshawar, Pakistan 22 years ago in May 1984. At that time, 2,400 leprosy patients were registered at the hospital. However, patients could only be admitted to the hospital after they developed serious complications since the leprosy ward had only 16 beds for admission. Treatment of leprosy requires various medical skills such as reconstructive surgery, plastic surgery, neurosurgery, dermatology as well as knowledge in social care services.

However, what they had at the hospital 22 years ago were one broken trolley, one gauze kettle, several broken pairs of forceps, one stethoscope that would hurt my ears when I wore it. Their method of disinfecting gauzes was to place them in a metal bowl and put it in an oven toaster. When the gauzes started to smoke, we would take them out of the oven quickly. If the gauzes had turned brown, they were disinfected. If they were still white, they were not. Thatfs where I started. Those who visited me at the hospital during those days were shocked to see the situation.

Peshawar-kai Head Office (Japan) has been very active in fund-raising and continued to provide financial assistance to my medical activities for all these years. Without their support, I wouldnft have been able to extend my medical services to benefit a growing number of patients.

Now, we have a well-equipped hospital where essential treatments for leprosy complications are available, including reconstructive surgery. With the help of local governmental organizations and agencies, our hospital has become a reassuring presence to those 7,000 registered patients throughout Afghanistan and north-western Pakistan.

You may think that our medical activity alone generates a lot of work and keeps us very busy. It is absolutely true, but we have also spent a lot of time and effort in pursuing non-medical activities for the last 22 years, hoping to achieve our ultimate goal which is to help local people attain better lives.

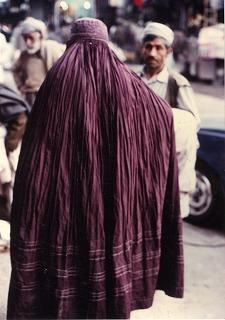

|

| £women with burqa |

One of such activitities is an effort to better understand the local people and their culture which are very different from ours. According to their custom, for example, young women are supposed to cover themselves with veils to avoid the eyes of male strangers.

This tradition made my medical work especially difficult because the early signs of leprosy appear on the patientfs skin. In case of male patients, it is easy because I can simply ask them to take off their clothes so I can examine their skin.

If a leprosy patient starts receiving a proper treatment at an early stage, this disease can be completely cured.

On the contrary, chances for cure are drastically smaller in female patients because they would refuse to expose their skin to male strangers, even if they are medical doctors.

No matter how inconvenient this custom may be, however, one has to be very careful not to make a mistake here. Many foreign workers often react wrongly in this kind of situation.

|

| £Japanese female workers |

Foreigners tend to impose their own value system on local people they are dealing with and draw a simplistic conclusion that they are right and local people are wrong, or they are superior and local people are inferior. Naturally, such a high-handed attitude will not be appreciated by the locals and, as a result, create unnecessary conflicts. At this point, some foreign workers would give up and desert their patients. I would like to ask to those foreign workers who would easily give up what they think will become of their patients who are left behind. As someone who has stayed behind with these patients, I am almost tempted to say to them, gWhy donft you take your patients back home with you if you are leaving. Didnft you come here wishing to help them?h

|

| £peshawar mission hospital, leprosy patients |

I often think that we, humans, arenft as free as we think we are. We are actually restrained by many things in our lives such as traditions, social relationships, nationalities, genders, places of birth, time we are living in and so on. These things restrict us from doing whatever we want to do no matter how old we are and where we live. There are limits in what we can do in life. I find it very important as a clinical doctor to understand that what I can do to my patients is limited yet I must still try to find best available solutions and do the best I can for them under the given circumstances. At the same time, I keep in mind that I should never impose my values on these people or be judgemental about their customs, traditions or cultures.

This is the guideline we strictly impose upon ourselves among the Peshawar-kai workers. To give you an example, we recruit female staff from Japan and have them attend to female patients, instead of criticizing their tradition of not exposing themselves to male strangers and doing nothing.

In 1979, 100,000-strong former Soviet troops invaded Afghanistan. During my first three years in Peshawar, from 1984 through 1986, the Afghan civil war was fought most fiercely. Peshawar is a border city and is also called, gthe city of Pashtunsh. They are the largest ethnic group in the region. A half of the 16 million Pashtuns live on the Pakistan side and the other half on the Afghan side. They are the majority group on both sides. They freely travel back and forth between the two countries. The civil war, which followed the Soviet invasion, generated six million Afghan refugees and half of them flooded into Peshawar and its surrounding areas. Reportedly, at least two million people, including 600,000 combatants, have been killed during the civil war. Our medical activities, of course, were greatly affected by this war.

Around this time, we ran a small-scale mobile clinic at refugee camps for a while and decided to change the way we operated our medical activities. Most Afghan villages with a high incidence of leprosy are located deep in the mountains. Where leprosy is common, many other infectious diseases such as typhoid fever, malaria, dysentery and tuberculosis are often found too. To make things worse, patients inflicted with these diseases are very poor and have no access to medical services. In such areas, it is very difficult to tell local people that we came to their village only to treat leprosy, but other diseases. Consequently, we decided to establish a model case of medical care specifically for rural areas in Afghanistan where no medical services are available.

|

| £at refugee camps |

Thus, providing our medical services in rural areas became one of our most important projects.

Statistics of Afghanistan are often unreliable. When we launched this new project, we had no idea about the demography of our target areas or what diseases were common there.

To make things more difficult, it was very dangerous to walk around the areas because of the ongoing war but it was the only option we had. The 2,400km-long border was not completely sealed off. So we walked up and down the mountains to learn about our target areas.

One day my staff and I reached an area called Nuristan, situated at 2,800 meters altitude, half way up the countryfs highest mountain, and local men came up to me and said, gWelcome from France.h They asked me if I was French. I had been asked if I was Chinese or Korean before, but never French. Later I was told that they had never seen foreigners before so they randomly mentioned a name of a foreign country they knew.

|

| £houses on mountain |

At any rate, this episode typically describes what it is like in rural Afghanistan. The capital city, Kabul, is very far away from these villagers both physically and mentally.

What was more interesting to me on that day was that, once I told them that I was Japanese, their attitude toward me completely changed. They began acting very friendly toward me. I later learned why. The country name of Japan in their mind was associated with the Russo-Japanese War that occurred a century ago. They also knew about Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Everywhere I went, no matter how deep in the mountains, villagers knew these things. I believe their respect toward Japan comes from the fact that they too have experienced misery through the western domination and that they have been deprived of peaceful life by that.

Hearing about a tiny, vulnerable country in the Far East fighting against a superpower in the Russo-Japanese War must have inspired these people during the past colonial era they experienced. They also displayed a deep sympathy for the Japanese victims of the atomic bombs. It was fortunate for me that they did not know that Japan had followed in the footsteps of her Western gteachersh later on and acted as if they were the forward-thinking guards of the Western countries by invading neighbouring countries.

The Soviet troops started to withdraw from Afghanistan in 1988. After the withdrawal was completed in 1989, Afghanistan remained a centre of the world news. A host of journalists rushed from all over the world with the expectation that they would be reporting on the immediate return of the three million Afghan refugees to their motherland. Contrary to their anticipation, no one went home.

|

| £refugee returning |

During this time, there were a lot of enthusiastic discussions about the reconstruction of Afghanistan. Over 200 aid organizations flocked to Peshawar from all over the world, spending tens of millions of dollars in two years. Ironically, no refugees returned home despite of all these international supports. Meanwhile, the civil war intensified and the Gulf War broke out. Immediately after this, most aid organizations for Afghan refugees in Peshawar closed their offices and left. This abrupt departure of aid organizations deeply disappointed Afghan refugees. Before long, Afghan communist government collapsed, and various armed political groups flooded into Kabul, seeking to take control of the capital. Meanwhile, the traditional system of autonomous rule made a comeback in rural areas. As soon as the Afghans became aware of this transformation, they began returning home on a massive scale.

In only seven months from May through December 1992, two million out of the 2.7 million refugees returned to Afghanistan with almost no foreign assistance.

Seeing the refugees coming back, we started opening our clinics, one after another, in mountainous areas. These clinics are still functioning today.

|

| £mobile clinic |

In 1998, after 15 years of commitment, we became aware that the problems we had been tackling would not be solved in the next 10 or 20 years. Therefore, we opened our base hospital with 70 beds in Peshawar so we could be rooted in society as a local institution there. Having this hospital in Peshawar increasingly helps us in running other projects both in Afghanistan and Pakistan since we can use it as the hub of our activities.

|

| £PMS |

In Japan, we are a voluntary organization or non-governmental organization. But in Pakistan, we are registered as a social welfare organization.

Afghanistan is truly an ill-fated country. On top of what has happened in the past, the country is now hit by the worst drought ever in history. According to the World Health Organizationfs estimate in June 2000, the drought has spread from the Central Asia to China, India, Pakistan, Iran and Iraq. Afghanistan is most badly damaged of all.

Twelve million people, more than half the population of Afghanistan, have suffered and are suffering from it. Four million Afghans are on the verge of starvation and one million might starve to death in the near future.

In some areas of Afghanistan, we have seen people walk for several kilometres just to get water, sometimes spending a whole day. Villagersf main property is livestock, but they had to sell their cattle to survive. They say 90% of whole livestock in Afghanistan was lost in year 2000. Vast farmland has turned into a desert. The number of internally displaced people and refugees rapidly increased. The countryfs agriculture has been seriously damaged by the drought. In the areas that surround our clinic, residents started evacuating their home villages.

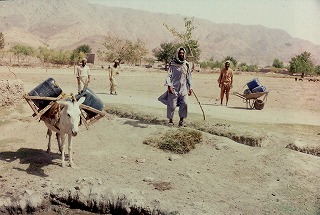

|

| £draught |

Most of the drought victims were children. The outbreaks of gastro-intestinal infections such as dysentery, amoebiasis and typhoid affected their young lives. So many children died of dysentery after drinking contaminated water. Their deaths are the results of the lack of clean water and malnutrition. We have seen many children expiring in their mothersf arms in our clinicfs outpatientsf waiting room. It wasnft an exaggeration when WHO warned that one million might starve to death due to the drought. Medicines canft cure malnutrition or solve water shortage problems. The situation was so desperate that simply trying to stay alive became a very difficult challenge for the Afghans.

Given this situation, feeding and keeping them alive became our biggest concern. We decided to worry about treating their illnesses later after their lives are saved from death.

|

| £well digging |

In July 2000, we mobilized the remaining villagers and started digging wells to obtain clean water. This was the beginning of our new project.

Although the locals already knew how to dig a well, they did not know what to do when they hit a large piece of rock. The water level was continuously going down. We had to keep digging to compete with the descending water level. We used land mines to break huge stones into pieces.

|

| £karez |

This was our very unique way of using landmines: We used them for a peaceful purpose.This project is still going on. By June 2003 we had worked at 1,000 sites in total.Currently, over 1,400 sites provide water to local population. Thanks to this project, nearly 300,000 villagers are still being able to remain in their villages.taken 7 months after the first picture was taken.

However, people cannot survive only on drinking water. Our next challenge was to obtain water for farming. Afghans have a traditional irrigation system called gkarezh which brings underground-water to cultivated land.

|

| £clinic in 2000 |

We revived 38 karezes as well as large-size irrigation wells in the last few years. These refurbished water systems produced green fields, and they still continue to do so. In this area, green fields continue to expand around these wells.

This picture was taken in September 2000. It shows the surrounding area of our clinic.

No one would be able to believe there used to be lush green rice fields here only a year earlier. We have irrigated these fields. The next picture was taken 7 months after the first picture was taken.

|

| £same clinic in Feb. 2001 |

This is the same place in February 2001. One thousand families had come home voluntarily. Green fields had spread quickly. This way, a water project has become a very important part of our activity.

In January 2001, the UN imposed sanctions against Afghanistan. Ordinary Afghans could not understand why they had to be punished in such a way. Before the sanction, I had believed that the world would not ignore the large-scale devastation the Afghans were experiencing for the first time in history. Contrary to my belief, the U.N. imposed sanctions on Afghanistan instead of providing aid to them. To make things even worse, they tried to impose sanctions on food in the beginning. Imagine how those starving people in Afghanistan felt about this. International aid organizations started evacuating their foreign personnel, although there were already very few of them that were still operating in the country. These sanctions definitely shunned Afghanistan from the other parts of the world. From then on, distrust toward foreigners spread among the Afghans.

|

| £food dispatching |

Following the September 11 terrorist attack in New York, news about Osama Bin Laden, the Taliban and other Afghan matters suddenly flooded the media all over the world. If you knew anything about Afghanistan, you would agree with me that bombing this country before the onset of winter was a criminal act. It was already feared that over 10% of the population might not be able to survive the severe winter that year. This horrible prospect led us to launch the gFund for Life.h Under this programme, we dispatched 2,000 tons of wheat and cooking oil which saved the lives of over 100,000 Afghans. Our brave Afghan and Pakistani staff carried out this dangerous task under a heavy bombardment by the U.S. forces.

|

| £popy farm |

As soon as the Taliban government collapsed, we started to witness the revival of lawlessness, opium production, fighting between rival warlords and starvation. Let me give you an example of whatfs happening in todayfs Afghanistan since it doesnft seem to be widely known to the world. If you come across a field of pretty flowers in Afghanistan, it is a poppy farm. Yes, the so-called efreedom and democracyf have unleashed many things such as heroin production, prostitution, crimes, and further starvation. Having seen foreign media not reporting this terrible reality to the outside world, I came to realize that it is possible in supposedly advanced countries to control media reports.

|

| £canal, green field |

Ifd like to point out here that we have always kept distance from any sort of authorities for all these years. Thanks to this, our activities have never been affected by volatile political climate. Whatever the power that be, we have maintained our focus solely on our programme and on serving the people in need. To me, restoring a self-sufficient life in rural areas is the most crucial task because I believe it will be the foundation of peace in the country. War is not the solution. Therefore, we are now trying hard to help the locals increase their agricultural production. We have no interest in getting involved with politics at all.

In March 2003, we launched the construction project of 14km-long canal in eastern Afghanistan. The canal is expected to irrigate more than 5,000 hectares of farmland which had turned into a desert because of the drought in the last several years. When the canal is completed, 150,000 farmers will be able to cultivate their land and stay alive in their villages. As of April 2006, the canal was completed up to 10 km. So far, 1,500 hectares of devastated land have been revived into farmland, and lush green field will continue to expand year after year.

|

| £canal construction site |

A number of villagers are busy working with pickaxe and shovels at the canal construction site every day and they are doing it to save their lives. It may be very surprising for foreigners to see all these men- members of different political parties, former pro- or anti-Taliban soldiers, supporters of the Northern Alliance and local employees of the U.S. army- working together at the site. This scene looks even ridiculous to me, considering the political dynamism taking place at the moment in this country. However, once their minds are set on a much larger goal, differences in opinions and political positions donft seem to matter anymore and the prejudice against one another could disappear. In their case, in particular, what are at stake are their very lives- all the other things are minor compared with the matter of life or death.

|

| £irrigation canal, water running |

This irrigation canal is carefully designed so that the local farmers will be able to maintain it by themselves for hundreds of years to come. We chose to adopt Afghanfs traditional method and mix it with the Japanese civil engineering techniques used for agricultural purposes in old times.

We intentionally avoided a costly, modern method.Inlet from the Kunar River: This is a copy of Japanfs classic goblique damh which has been working for more than 250 years.The main irrigation canal (2 years after construction); Jakago (stone cages) are used in many sections of the canal to protect the canal from rapid stream. 100,000 willow trees were planted so that their roots will protect Jakago from falling apart.A water reservoir for sedimentation; muddy water becomes clean here.A Japanfs traditional water gate: Water flows over the wooden plates and the volume of water will be control here manually.

|

| £jakago |

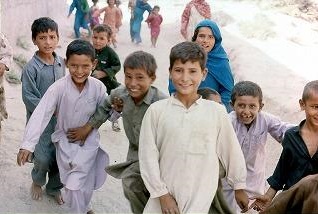

Every time I give a lecture on Afghanistan, I show some slides to tell my audience that the Afghan people donft always look depressed. To me, the people in developed countries such as Japan often look more depressed or unhappier. The Afghans have such great smiles that those of us who are helping them get inspired and encouraged in return.

We tend to think we could do better if we had more. However, the more you possess, the more despondent you become. In Japan, people say we are facing a serious recession.

When I first heard someone say that, I asked the person how many people had died of starvation because of the recession. His answer was that no one starved to death, but over 30,000 people had committed suicide.

|

| £Afghan kids smiling |

When I first started my medical services in Pakistan 22 years ago, what brought me there was a ghumanitarian motivationh. I wanted to save people in need over there. Looking back at the past 22 years, however, I came to realize that the more important thing than the fact that we helped those people is that we, those who helped these deprived people, have been helped by them in many ways. At least, I could free myself from an illusion that violence and money can solve any problems that men face in the world, thanks to my experience. Also, I am not fooled by the justification that violence is necessary for the sake of democracy and modernization. True happiness for mankind should be realized not through violence or money, but in a humane way.

I consider myself fortunate to be able to discover this truth and speak about it, while the whole world seems to be confused by the campaign of the war on terror. There is no doubt that my experience in Afghanistan helps me see things more clearly. To me, it is time we seriously contemplated and found out what is truly needed for mankind and what is not. Whatfs taking place in Afghanistan today is teaching us a lot about this.

What has happened in that country also reveals to us that our civilization is nothing more than a thin layer over barbarism we, humans, have exercised for a long, long time since ancient times. The real enemy we have to fight is in our minds, not outside.

With this, I would like to conclude my presentation. Thank you very much for your attention.

|